by Jay Kulkarni and Susan Thomas.

The economic well-being of households is primarily about their ability to spend on consumption. Household consumption is dominated by what the income of the household is, but not limited by it. Households that spend less than they earn, build their savings. Households that spend more than they earn either borrow or draw down on earlier savings. There is a big difference in the life-cycle possibilities between households that manage to save versus those that do not. In this article, we analyse a panel dataset of Indian households to understand what differentiates households who live within, or beyond, their means.

An often discussed measure of the household's income-consumption dynamic is the `marginal propensity to consume' or MPC, which is the marginal change in consumption for a marginal change in income. The MPC is a valuable part of the toolkit of macroeconomics. An equally important measure is the 'average propensity to consume' (which is abbreviated as APC). This is the fraction of disposable income that the household consumes. The APC shows the income-consumption dynamics of a household in a stated time period. When the APC is below 1, the household is saving, and on average, building up its wealth. There is a clear line between low APC households (i.e. those with APC below 1), who are building up wealth, vs. the households that are not.

In an advanced economy, we think of the APC as a part of life cycle optimisations. When an affluent and financial unconstrained household is young, it builds up savings (i.e. low APC), and then it dis-saves in old age (i.e. high APC). In a poor country, we see many households who are dis-saving even when they are young. Building up wealth versus drawing down wealth takes on a different character in the context of a low middle income economy (Badarinza et al, 2019).

Aggregate facts about household APC, and its covariates, are an important element of understanding India. This article aims to establish such facts. What is the average household APC in India? What fraction of households have a low APC? Do higher income households have a low APC? Do low APC households have lower income volatility? Are low APC households systematically older households? What is the connection between financial inclusion and household APC?

Data and Methodology

The measurement of consumption is an important feature of many government statistical systems. Aggregative statements are derived from the national accounts. The best information about households is found in advanced economies such as the US (Consumer Expenditure Surveys) and the UK (Family Resources Survey), which are observed at annual frequencies.

Less is known about Indian households. In recent times, better measurement of households has commenced in India. One such dataset is the Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS) published by CMIE, which began in 2014 and now surveys about 200,000 households every year, thrice a year. For this article, we focus on their 2023 and 2024 data.

Computing an APC can be done at different frequencies. In this article, we compute the APC at both monthly and annual data.

Average household APC in India using annual data

We start at the annual APC and establish basic facts. Household data is hard to measure, given difficulties in survey administration, in the interest of the household in offering information, and in the correct recollection by the household. Hence we show a robust estimator of the mean APC across the values obtained for each household. Table 1 reports this value along with other summary statistics. The big fact that we take away is that the (robust mean of the) APC was 0.64 in 2024. If (1 - APC) is the savings rate, this implies a savings rate of 0.33 percent in 2023 and 0.36 in 2024.

Table 1: Distribution of annual household APC in India, 2023, 2024

| 25th | 50th | 75th | Mean | Std.Dev. | Fraction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| with APC<1 | ||||||

| 2024 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.33 | 94.23 |

| 2023 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 91.79 |

Going deeper into cross-sectional variation and higher frequency observation

Households may have an annual APC < 1, while having some months where APC > 1. For example, a farming family may be above the water when viewed at the level of the year, but it may earn income only at the Kharif harvest, and run with APC > 1 for all other months. We now define a `Low APC household' as one which lives strictly within its means, where every monthly APC (and therefore the annual APC) is less than 1. Using this definition, we partition the data into Low vs. High APC households.

Table 1 shows that 94.23 percent of Indian households in 2024 are at an annual APC < 1. But when we switch to this modified view of the APC within the year, the picture changes. In this perspective, 54 per cent of Indian households in 2024 are low APC. For 2023, this value was 48 per cent.

We also observe the age of the household head, as well as other household features such as the fraction of members who are dependents and the fraction who are employed. To make numbers comparable, we adjust prices for inflation using an all-India series re-based to December 2024, and use per-capita numbers to account for different household sizes in the sample.

We construct a measure of household income volatility, as the standard deviation of the percentage monthly changes in household income. We construct a financial participation score as in Palta et al (2022). This is the fraction of the number of financial assets households own, out of the 10 that dataset records. The debt status of each household is also separately observed.

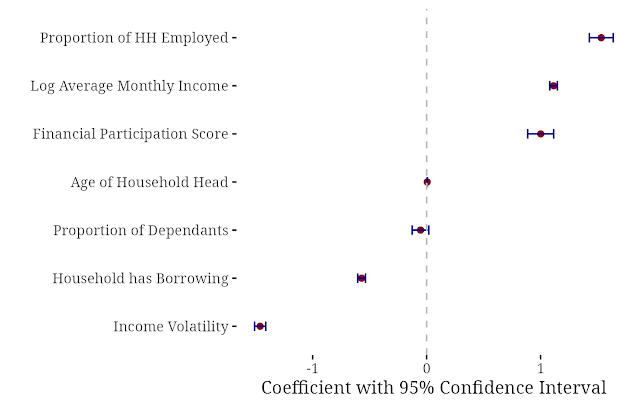

We then explore cross-sectional variation by estimating a probit model to predict a low APC household based on the annual data. All explanatory variables are contemporaneous. Figure 1 presents the estimated coefficients from this regression. In this figure, the vertical dashed line indicates the 0 value of the null hypothesis. Any coefficient on the right is positive, and to the left the coefficient which can be used to answer the questions raised above. The distance of the error bars from the 0 value line shows that the coefficient is statistically significant, and influential in the probability of the household being a low-APC household.

Figure 1: Factors affecting the probability of being classified as a low APC household

What do we see here?

- Do low APC households have higher income?

The coefficient of log income is positive and significant. The higher the income, the higher the probability that the household is low APC. - Do low APC households have higher income volatility?

Income volatility has a negative and significant coefficient. This means that higher the volatility of income, the lower the chance of the household being low APC. - Are low APC households older?

The age of the head of the household is a proxy for the age of the household. The coefficient for this is close to zero (value of 0.0052) but is positive and significant. Households with older heads tend to be low APC. This income-consumption pattern is consistent with the life-cycle hypothesis of Modigliani and Brumberg (1950), or the permanent income hypothesis of Friedman (1957). - Do low APC households have a better financial participation score?

The household financial participation score is a useful way to think about the asset side of the household balance sheet (Ghosh and Thomas, 2022). This coefficient is positive and significant. In addition, the presence of borrowing tends to run in the opposite direction (borrower households are more likely to be high APC).

Discussion

We have a new fact about Indian households: About half of these have at least one month a year where they live beyond their means. Many of the results that we see here are consistent with empirical findings in other countries (Goodman and Webb, 1995, Blundell and Preston, 1998, Gorbachev, 2011, Fisher et al, 2020). Higher income, higher fraction of members employed, higher financial participation score, older households, lower income volatility, lower fraction of dependents, and not having debt, correlate with being a low APC household.

The trajectory of income, savings and wealth by an affluent, financially unconstrained household, operating in a well functioning macroeconomic and financial system is well-established. We expect households to save when they are young, and dis-save when they are old. In the Indian setting, such behaviour is perhaps the privilege of a small number of households who face more complex financial planning problems within the year.

In thinking about households in India, the distinction between households that are adding to their savings versus the households that are not, seems fundamental. It has far-reaching consequences for the life of a household. From the viewpoint of governments and firms, this is an interesting distinction which can be applied when thinking about households. This article is a first look, based on novel mechanisms of measurement, covering two years of data only. More research is needed to obtain insights into the causes and consequences of these phenomena. What is the dynamics of low APC across time? What kinds of households are able to achieve low APC on a sustained basis? How does the build-up of household wealth reshape the decisions of a low APC household?

References

- Cristian Badarinza, Vimal Balasubramaniam and Tarun Ramadorai, The household finance landscape in emerging economies, Annual Review of Financial Economics, Volume 11, pages 109-129, 2019.

- Richard Blundell and Ian Preston, Consumption Inequality and Income Uncertainty, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 113, Number 3, May 1998, pages 603-640.

- Jonathan D. Fisher, David S. Johnson, Timothy M. Smeeding and Jeffrey P. Thompson, Estimating the marginal propensity to consume using distributions of income, consumption and wealthJournal of Macroeconomics, Volume 65, 2020.

- Indradeep Ghosh and Susan Thomas, Financial inclusion measurement: Deepening the evidence, Chapter 9, Inclusive Finance India Report 2022, 17th edition, pages 117-125, January 2023.

- Alissa Goodman and Steven Webb, The distribution of UK household expenditure, 1972-1992, Fiscal Studies, Volume 16, Number 3, pages 55-80, 1995.

- Olga Gorbachev, Did household consumption become more volatile?, American Economic Review, Volume 101, Number 5, August 2011, pages 2248-70.

- Geetika Palta, Mithila A. Sarah and Susan Thomas, Measuring financial inclusion: how much do households participate in the formal financial system?, The Leap Blog, 3 July 2022.

Acknowledgments

Jay has just wrapped up his masters in economics from Università Bocconi. Susan is senior research fellow at XKDR Forum. We thank Geetika Palta for help on working with CPHS, and Ajay Shah for positioning and inputs.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please note: Comments are moderated. Only civilised conversation is permitted on this blog. Criticism is perfectly okay; uncivilised language is not. We delete any comment which is spam, has personal attacks against anyone, or uses foul language. We delete any comment which does not contribute to the intellectual discussion about the blog article in question.

LaTeX mathematics works. This means that if you want to say $10 you have to say \$10.