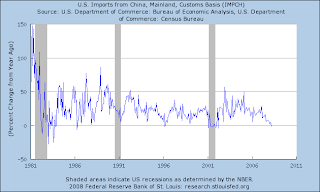

Before we get to the arguments, here's a picture with the key facts from Martin Wolf's recent FT column on the subject:

Explanations that don't persuade

Hypothesis: The spike in world food prices is caused by increased demand in China and India, particularly the shift towards consumption of meat as people get richer. My problem with this explanation is that it doesn't explain why the price index for major food crops was stable at 100 from 1990 till 2005, and spiked thereafter. China and India had a massive transformation of incomes and the structure of the food basket from 1990 to 2005.

Hypothesis: It's the evil speculators. Speculators who anticipated higher prices would have held more inventory. But the graph shows that inventories have dropped from 2000 onwards. There was less hoarding, not more. [Ken Rogoff]

The bulk of trading on futures markets is speculative: but for every buyer on a futures market there's an equal and opposite seller (by definition). A bigger futures open interest has no net effect on prices.

More generally, futures markets have been around for over a century and grown steadily over the 1990-2008 period: it's hard to blame them for the spike in prices starting in 2005.

Yes, there's a new phenomenon of commodity funds and hedge funds trading in commodities. But these numbers are just tiny when compared with the global agricultural trade. And if they had held a lot of inventory, it would have shown up in the inventory series above - but total global inventories went down and not up.

Hypothesis: As the world gets richer, price volatility of non-storable agricultural products gets bigger

Here's one phenomenon which could play a role in deciphering what happened. Suppose, for a moment, that a commodity is not storable. And, we know that given the lags between sowing and harvest, in the short term, a price innovation can induce no supply response. When an imbalance between supply and demand arises, prices move to clear the imbalance. How far do prices have to move? Prices have to move as much as is needed for demand to get crimped, so as to equalise supply and demand.

Now consider a product such as wheat. When there is an upward shock to the price of wheat, rich people just do not reduce their consumption. A naan or a baguette that weighs 0.1 kg has an embedded cost of wheat of USD 0.04 or Rs.1.6 (assuming wheat is at $400/MT). When an affluent person buys or makes a baguette or a naan, a very large change in the price of wheat generates no change in consumption. A 50% change in the price of wheat sounds like a lot: but it drives up the embedded wheat cost in the baguette/naan by USD 0.02 or Rs.0.8 - this would be insignificant for affluent people. Their demand is inelastic.

When demand is bigger than supply for a nonstorable commodity with zero short-term supply elasticity, prices would rise as much as is needed to close the gap. Demand can only shrink when some people get pinched and ease up on consumption. These are the poor. Poor people are the shock absorber that stabilise prices for non-storable agricultural commodities.

When potato prices went up in an Irish famine, poor people consumed more not less, because the income effect dominated. Could that happen with poor people and wheat? It is useful to think of three levels of affluence:

- The first would akin to 19th century Ireland, with poor people primarily eating wheat, and we can get odd effects. We could get such behaviour today with the really poor. In 1985, I happened to be an honoured guest at a hamlet in Western Maharashtra. The lunch they served me was: flat bread made of coarse grain. That's it. There was nothing else, just powdered red chili for flavour.

- The second case is a person who's rich enough to eat some meat, but would cut back on meat when it got expensive. This kind of person generates high price elasticity of demand for grain because of the 2:1 or 8:1 ratios between meat and grain, which imply that for each 1 kg of meat that he backs away from, 2 or 8 kg of grain is freed up. Hence, in the early stages of food-feed conflict, when people have started dabbling with meat but aren't yet price insensitive about it, the price elasticity of wheat demand goes up sharply.

- The third case is a person who is rich enough to eat meat and is price insensitive about it. A buildup of more people in this third case reduces price elasticity of demand.

My story is about a world where there are very few people in the 1st case, and an increasing transition from the 2nd case to the 3rd case. GDP growth yields fewer poor people who respond to higher wheat prices by purchasing less meat or wheat, i.e. we have less of a shock absorber. That generates a reduced elasticity of demand of wheat. So prices have to rise by more in order to clear a supply-demand imbalance than was required in the past when there were more poor people who would adjust.

In the bad old days, people in China and India supplied the world with a large shock absorber, a large mass of poor people who tightened their belts when prices rose. This gave higher global demand elasticity and reduced price volatility. From the late 1970s, economic reforms in China and India have given greater affluence and thus diminished this shock absorber.

Here's a picture of the moving-window volatility (calculated using four-year windows off weekly returns) for wheat:

This does seem to show a longer term phenomenon of increasing vol.

Storage

Now let's bring in speculators and storage. Suppose commodity volatility went up in this fashion when affluence increased. This should generate increased profitability for the speculative strategy of holding inventories of food and opportunistically waiting for the next great price flare-up. Call this hoarding or call it buffer stocks: the bottom line is that large inventories stabilise prices.

The cost of holding in recent years was unusually low given the low interest rates. (As an aside, the direction of effects here runs opposite to what Jeffrey Frankel has been talking about). But the data shows that hoarding didn't go up; on the contrary inventories have dropped from 2000 onwards.

The puzzle is : why is there so little speculation? Why did speculators in 2000-2005 do so little hoarding? Hoarding would have smoothed out prices: purchases in 2000-2005 would have given higher prices then and sale in 2008 would have given lower prices today.

To buy 10 million tonnes of wheat in 2005 and hold requires a bit of capital. At USD 300/MT, this would require putting down $3 billion plus a flow of storage costs. Who were the kinds of players who were setup to evaluate such a trade? What kinds of leverage was available to them, to juice up their return on equity? I don't know enough about the field: was there an abundance of such players and did they have enough leverage?

Were we hitting limits of arbitrage? Was insufficient capital being put into these speculative strategies for some reasons that are linked up to the institutional structures of finance? I am reminded of the difficulties of uncovered interest parity (UIP) on the currency markets. The `carry trade' is an equilibriating response; it would tend to make UIP work. Perhaps too little capital is put into the carry trade relative to the massive size of the currency market, thus generating violations of UIP.

Is a similar phenomenon going on here? Perhaps the massive pools of financial capital that are able to hold large inventories (a.k.a. buffer stocks) weren't being deployed into commodities on a scale required to have inventories that are large enough to stabilise the global food market. If so, the solution would involve more capital with commodity funds and hedge funds that trade in commodities.

Putting together

Perhaps what happened was like this. There was a string of supply shocks - things like ten consecutive droughts in Australia, a small switch towards biofuels.

If these shocks were anticipated in 2000-2005, then this points to institutional failures where the financial / commodity firms were not able to galvanise themselves to do enough hoarding. Alternatively, if these shocks were not anticipated in 2000-2005, then the future outlook had to be benign, which led to a rational drawdown of inventory, i.e. low buffer stocks, in the hands of the speculators.

Prosperity had risen over the years, giving unusually inelastic demand -- the consumers of China and India who have long contributed to elasticity of global demand by tightening their belts were less poor and less willing to tighten their belts. With fewer people willing to adjust, prices had to move a lot to clear supply and demand.

What comes next

I am optimistic about what the future holds.

High prices have a way of inducing far-reaching supply responses on the medium term and long term. We have been surprised, again and again in the past, at the cleverness with which producers responded to higher prices by producing more. When the Hunt brothers tried to corner the world market for silver, they were astounded at the quantities of silver that were brought into the market by way of a response to higher prices. High prices of petroleum products increases the use of camels in transportation.

In similar fashion, high wheat prices can even make Afghan poppy farmers switch to growing wheat! Vast tracts of land in Russia and India have low yields: High prices will give incentives to entrepreneurs to find ways to use this land better. Over the coming two years, a large supply response could come about. Something big might already be afoot: an 8.2% rise in world wheat output is projected for 2008-09, and surely some of it has to do with the incentives put out by high prices.

These events seem to have helped reduce the informational and institutional gap between finance and commodities. A greater convergence between the financial world and the commodities world, through new structures such as commodity funds or hedge funds that deal in commodities, would bring resources commensurate with the size of these markets into play. You choose whether you want to call this stabilisation, hoarding, speculation or buffer stocks.